'Are we going in or we staying here?' Chaos, confusion captured on Uvalde police bodycams

Pistol in his hands, Uvalde school police officer Ruben Ruiz pushed his way through the knot of heavily armed officers waiting around a corner from where his wife was dying on the floor of her classroom.

"She says she's shot, Johnny," Ruiz said, imploring Constable John Field to let him through.

Field refused, snaking an arm around the distraught man’s neck, stopping him from trying to rescue his wife. As many as a dozen officers were crowded in the hallway, waiting to be told to make a move.

They didn’t know how bad the scene would become. But Ruiz did.

From her classroom, Eva Mireles had called her husband. She had been shot, she told him, and she was dying.

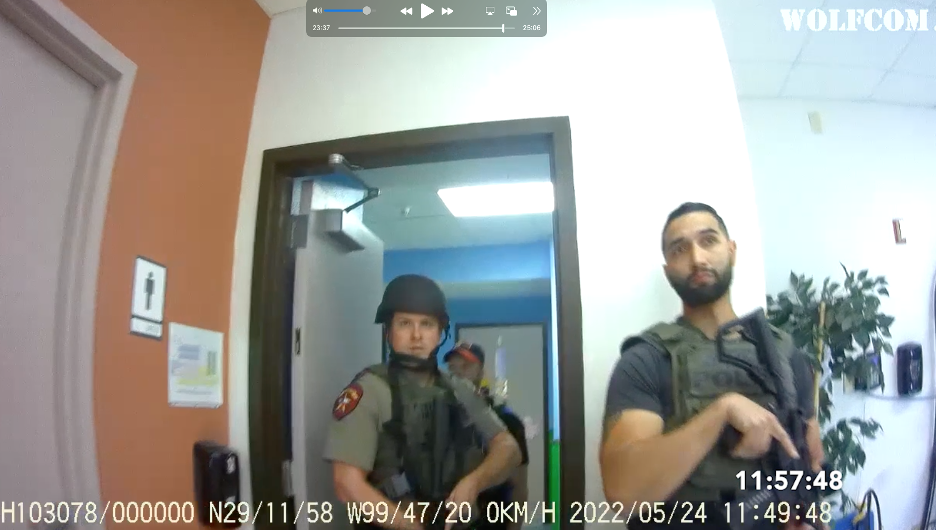

That moment between Ruiz and Field is one of many revealed by newly released police bodycam footage showing the police response to the school shooting May 24 in Uvalde, Texas.

The camera footage provides an up-close view of the actions of the officers who were among the first to arrive that day.

The police response began after a gunman entered Robb Elementary School with a semi-automatic rifle, pushing into two adjoining classrooms, 111 and 112. His rampage did not end for 77 minutes, when later-arriving federal officers breached the classroom door and killed the shooter. Nineteen students and two teachers died in the attack on Robb Elementary.

FOR SUBSCRIBERS: In Uvalde, moments of silence, yet so much left to say

The police response has drawn wide condemnation. A preliminary report from the state’s House of Representatives, released this week, skewered every level of the law enforcement response to the shooting May 24, starting with the school district’s police chief, Pete Arredondo. It concluded that some victims might have survived if authorities had attempted a rescue earlier.

The report took care to note that it found no malice or ill motive by any responding officer. “Instead,” the reporting committee said, “we found systemic failures and egregious poor decision making.”

The bodycam videos, released by Uvalde city officials, identify six officers by name and carry a disclaimer that they have been edited to protect victims and witnesses.

Uvalde officers arrived at the school urgently, knowing that the children and friends of colleagues, and in some cases their own relatives, were inside.

From their first moments, the videos show widespread miscommunication among officers about the threat the school faced, what tactics they would use to end the standoff and even whether anyone was negotiating with the gunman.

The footage shows police calling for reinforcements with additional firepower, shields, incendiary devices, gas masks – gear they never used.

It reveals poignant moments amid the chaos, as officers shuffle incongruously past cheery school billboards and code-of-conduct signs.

Some moments turn heartwarming as officers attempt to free teachers and students hiding inside classrooms, comforting children even as they urge them to run: “Quickly, sweetheart, quickly.”

Others turn heartbreaking – as when the distraught Ruiz tried to push through the crowd. Field stopped him and guided him to the exit door, where he was disarmed.

Throughout, the footage shows officers struggling to find their own roles in a situation without a plan.

Officer Justin Mendoza, his chest heaving as he runs onto the school campus, exclaims to his colleagues a question that became a haunting prelude to the next 70-plus minutes:

“This is f---ed. Hey, are we going in or we staying here? What are we doing?”

EXCLUSIVE VIDEO: Surveillance footage obtained by Austin American-Statesman

VISUAL TIMELINE: Latest details and analysis

More equipment

Through the first 15 minutes on the scene, Sgt. Daniel Coronado repeatedly called for more firepower and protective equipment.

He wanted flash-bangs that could stun a gunman. He wanted a mirror to peer around corners and a glass-breaker to help evacuate children who were locked down in other classrooms.

As Justin Mendoza entered the school building, he offered, “I’ve got a rifle. Who’s got a rifle up there?”

Fellow officer Jesus Mendoza, a few minutes after entering the school’s west building, hustled back outside to call to a colleague. “Hey, Saucedo,” he shouted, “they need your rifle!” The other officer handed off the weapon. "It's hot," he warned before he flipped on the rifle's safety switch, then "OK. Safe safe safe."

Jesus Mendoza carried the gun back inside and handed it to another officer.

Throughout the early minutes, officers discussed protective shields.

Once inside the school hallway, Justin Mendoza’s video captured another discussion.

“Somebody get those shields,” one voice called.

Then a decision to do nothing. "Wait, Javi, just wait,” someone in the hallway said.

Another officer remarked, “There’s no active shooting, stand by. Someone can be hurt, so stand by.”

"We all want to get in there, Javi," the voice in the hallway said. "We all want to get in there, trust me."

The House report noted that four ballistic shields arrived from 11:52 a.m. to 12:21 p.m., although only one of them was rated to provide protection from the shooter’s high-powered rifle fire.

By then, other officers were discussing tactics such as using CS gas, a chemical irritant. “Do y’all have CS? CS gas? To gas him out?” one arriving Border Patrol agent asked.

Later, as seen in Justin Mendoza’s video, a uniformed officer rushed into the school carrying a crate of gas grenades. Someone asked, "We don't have gas masks?"

"No," another responded.

"Do you have y'all's masks?" a third yelled down the hallway.

Voices on the police radios called for flash-bang grenades. “We’re definitely going to need some flashers, some flash-bangs, if we have them,” one person said.

As the gear piled up, an officer in heavy camouflage gear asked, "The subject? No one knows where the kids or anything else is at?" Another replied, "Yeah, there's a student in there talking."

Over and over, officers tested keys that wouldn’t open classroom doors and called for someone to deliver a Halligan tool or other device for breaking down doors. The House report noted that no one called the school principal, who had a master key.

Soon, the school was inundated with gear and firepower, much of it just outside classrooms 111 and 112.

A helicopter arrived about 30 minutes into the saga, providing air surveillance while the beat of its blades overhead added to the chaos.

Shortly before noon, Justin Mendoza’s video showed, officers set up in the hallway with a protective shield.

"You don't want to make entrance?" an officer asked.

Another responded: "We're waiting. We've got a negotiator, and we're waiting for more shields."

MORE: How aggressive border control tactics in Texas contributed to inaction

MORE: Uvalde families deserve the Texas House Committee report in Spanish. Here it is.

More officers

As the gunman opened fire in a classroom, some of the officers stationed outside in the hallways shuffled backward, rifles and guns raised.

One of them, Sgt. Eduardo Canales, head of Uvalde’s SWAT team, put a hand up to his face, then pulled it back down. A small drop of blood appeared on his middle finger. As he raised his hand to feel his head, more blood appeared.

“Am I bleeding?” he asked the other officers.

Canales’ bodycam recorded no response from his fellow officers, just a faint voice in the background saying ”my wife’s classroom” as Canales went outside to inspect his injuries.

He was bleeding from his ear, he discovered, although neither he nor the officers in the recorded footage could tell how he got the injury. Investigators concluded he was hit by fragments when the gunman shot through a wall.

“We gotta get in there. He’s shooting, we’ve got to get in there,” Canales said, barely a minute into the recording.

Within seconds, he was on the phone with an unidentified person, asking for help.

“This guy is actively shooting. Just giving you guys a heads up because the more help, the better,” Canales said.

As minutes ticked by, no officers entered the classroom, but others continued to call for backup.

In the first hour, Coronado repeatedly called for other agencies, including the Border Patrol and the Department of Public Safety.

Officers swarmed to the school – 376 of them in all, from law enforcement departments across the state at all levels, according to the report.

There were so many that Coronado advised arrivals that reinforcements weren’t needed inside the school, but they could assist with perimeter crowd control.

Bodycam conversations indicate a sniper was positioned for a potential shot through a window.

Over the phone, Arredondo advised, “Something to think about if you get a shot." Coronado joined in, "We need to get a visual on him first."

School police repeatedly told others they were waiting for a Border Patrol tactical team to go after the shooter.

"Are we just waiting for BORTAC? What's going on?" one officer asked in Justin Mendoza’s video footage.

"I've got BORTAC on the way,” another officer responded. “I need an (officer in command) out here, I need someone to make calls."

When BORTAC arrived nearly an hour into the standoff, members didn't immediately launch the assault.

When one officer asked if the federal team was ready to go, Coronado answered, "We're good.” Then he said, “We don't have a key. He probably has it barricaded anyway."

A few minutes later, Arredondo reiterated, "We're ready to breach. Door's locked." He began testing a set of keys to see if they’d open a classroom door.

Ten more minutes went by. On the phone, Arredondo told someone, "We're having a problem getting in the ... room. ... Yes, sir. ... Yes, sir."

For 40 minutes, Arredondo was consumed with finding a master key to open the classroom door. The House report concluded the police chief was so fixated on this task that when Coronado warned Arredondo to stay out of the hallway to avoid potential gunfire, the chief snapped, “Just tell them to f---ing wait.”

Wasting those precious minutes on keys was a mistake because it delayed the breach of the classrooms, the House committee concluded.

No one had checked to see whether classrooms 111 or 112 were locked. Testimony revealed officers largely assumed the doors were locked because of school lockdown policy. But Room 111 had probably been unlocked the entire time.

MORE: Uvalde suspect, isolated and bullied, was teased about being 'school shooter.' Then he bought guns

No plan

In the footage from officer Jesus Mendoza, police gather outside the school’s main entrance. An officer remarks, “You want to go in there?” Then he adds a rejoinder: “Nah, what if he comes around?”

Officers captured in body camera footage repeatedly asked one another about a plan and shared tips that turned out to be wrong.

About 17 minutes after Jesus Mendoza arrived at the school, after he had followed a line of other officers into the hallway beneath the “Biblioteca” sign dangling from the ceiling, he stood near a group around the corner from the shooting scene.

An officer pushed past him, remarking, “Hey, Pete’s in the room with him.” A few minutes later, another remark, seemingly also about Chief Arredondo: “He’s going to be incident commander right now.”

The House report found that many officers were told similar news.

Through much of the first hour, officers were confused about whether children were in classrooms with the shooter, though early on, a dispatcher announced that class was in session at the time of the assault.

Coronado heard the news and gasped, “Oh, no. Oh, no.”

Misinformation was heightened by uncertainties and fears – particularly the possibility that more than one shooter was involved.

After helping dozens of children escape classrooms through broken windows, Coronado fretted to another officer, “I don’t know if there are two shooters or not.” Still, he went into the school and checked classrooms for more assailants, urging colleagues, “Cover me. Cover me.” As he opened one door, Coronado called out, “Uvalde police,” then aimed a flashlight beam through the darkened classroom, which was empty.

Throughout the 77-minute incident, the flow of misinformation left officers confused about what they were facing: an active shooter or a barricaded subject.

Arredondo said he believed that they had cornered the shooter. As he told the House committee, he had checked Room 110, which had a light on but was empty. Arredondo assumed wrongly that the other classrooms might be empty, too.

That meant, he thought, that they had the shooter cornered, he told the House committee..

As seen on the bodycam video, Coronado and other officers tried to initiate contact with the gunman by yelling out in English and Spanish.

"Sir, if you can hear me, please put your firearm down,” an officer shouted. “We don't want anybody else hurt. ... Responde, por favor."

Ten minutes later, after learning the shooter’s identity, the officer called out again: "Mr. Ramos, can you hear us? Mr. Ramos, please respond. ... Please don't hurt anyone. These are innocent children."

It is unclear whether the shooter answered.

Heart-wrenching moments

Outside the school, Uvalde police officers tried to guide rescue workers and frantic parents, even though the officers knew next to nothing about what was going on inside.

“Has he been neutralized?” one officer on the edge of the perimeter asked another in a pickup before letting him through a closed-off street adjacent to the school.

The officers in the camera footage pieced together what was going on inside the school from periodic updates from a dispatcher, who said police had one shooter “in custody.”

A police officer identified as Martinez repeated this to another officer and a father standing in the middle of a closed intersection. The news did nothing to change the frazzled expression on the face of the father, who said he had not one but two children at the school.

“I have twins,” he said. The father had been in contact with one child’s teacher. “But the other one, he had a sub.”

“Did you tell your wife to go to the civic center?” Martinez asked, repeating the instructions officers had given each parent trying to get to the school.

“Yeah, I did,” the father said, nodding his head and shrugging his shoulders before turning his gaze toward the school.

The two men understood each other. The evacuated students were going to the civic center, but the father couldn’t bring himself to leave.

“I feel the parents,” Martinez told him. “Because I have a kid, too."

Though the body camera footage revealed bad information, the massing of useless equipment and the confusion of the day, it also revealed tense human moments, both inside the school and on the streets outside.

In the hallway, Jesus Mendoza’s camera lingered on a poster outlining the code of conduct and its acronym, ROCK: Respect others. Own our behavior. Choose safety. Know our responsibility.

About 20 minutes after arriving at the school, he and other officers began checking classroom doors along the hallway. They had already passed by and stood outside these doors.

They turned back and rattled handles, finding that either the rooms were empty or whoever was hiding behind the door was not letting police in.

An arriving officer in a vest with a yellow “sheriff” label asked, “Are there kids in here? Where the kids at?”

Jesus Mendoza replied, “Well, nobody’s opening the door. Which is right. But, um.”

Both men seemed to recognize that lockdown protocol may have dictated teachers not open the doors to them. They knocked on the door, then moved on.

Across the hall, officers went into the boys bathroom, around the corner from the scene of the shooting.

In security camera footage taken earlier, one child could be seen in the hallway, peering around the corner as the shooter arrived. When shots started, he fled offscreen.

According to the House report, Special Agent Luke Williams of the Department of Public Safety ignored a directive to stay outside and fortify the perimeter. Instead, he walked into the building and started clearing rooms. He found a boy hiding in a bathroom stall, his legs tucked out of sight from the floor. The child refused to come out right away. He had been taught to demand to see a badge.

Williams complied, poking his badge under the stall for the boy to inspect.

The body camera footage captured the child emerging from the restroom. As he jogged down the hallway toward the exit, Jesus Mendoza urged him on: “Let’s go, boss, let’s go.”

Elsewhere, officers decided to smash windows from the outside to evacuate students.

Justin Mendoza hustled outside the school and helped pull students out, telling them to pull up their legs to fit through the window.

"You're being a trooper, brother, you've got this,” he told one student whose identity is concealed in the video. “Come on, let's get you out of there."

Officers lifted a crying girl through shards of glass. "Quickly, sweetheart, quickly,” one of them told her. “It's OK, baby, it's OK. Run! Run! Run!"

At the police perimeter, a man in a blue shirt and Houston Texans ball cap stood in front of an officer, wiping tears from his eyes.

“You don’t know what happened in there?” the grandfather asked.

“Right now, we don’t have any details,” the officer told him.

The worst details were only beginning to emerge, even for officers inside the hallway.

About a quarter before noon, as officers amassed in the hallway, Ruben Ruiz approached Jesus Mendoza. “The classroom he’s in,” Ruiz said, “is my wife’s classroom.”

About 15 minutes later, Ruiz pushed through the line of officers for the last time. “She says she's shot, Johnny,” he said before being turned around and sent back outside.

Nearly another hour went by before officers lined up to breach the classroom door. As officers donned blue surgical gloves, Justin Mendoza said to another officer, “There’s a kid calling from the room saying there’s victims in there.”

He asked a colleague, “Is it Ruben’s wife?” Getting the confirmation he feared, he swore under his breath: “Motherf-----.”

Minutes later, the team breached the door, killing the gunman. Ruiz’s wife, Eva Mireles, was bleeding on the floor. Crews were ready to rush her to a hospital. But it was too late.

Contributing: Andrea Ball and Josh Susong

More from USA TODAY

FOR SUBSCRIBERS: An electric bike rode into the backcountry. Now there's a nationwide turf war

FOR SUBSCRIBERS: She lost her sense of smell. It almost ended her business

FOR SUBSCRIBERS: From Potemkin to Putin: What a centuries-old myth reveals about Russia's war against Ukraine

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Uvalde body camera footage shows police confusion amid Texas shooting